Procedural dramas like “CSI” have convinced Americans that forensic science is equivalent to pure, unassailable fact. After all, tests and evidence don’t lie, even if people do. But sadly, this belief in the infallibility of forensic science is misplaced and made all the more dangerous by the fact that it is so common.

While some forensic tests are highly reliable (like DNA tests performed under correct conditions), some forensic tests cannot even be called “science.” In the middle, there are forensic tests and investigatory techniques that can be scientific but are far from perfect. Arson and burn-pattern investigation are good examples of the latter.

Innocent man freed after 14 years in prison

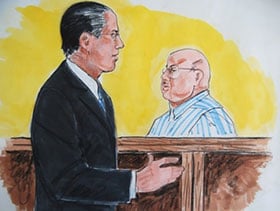

A recent article in the Washington Post told the story of a 29-year-old man from a tiny town in West Virginia who was convicted in 2005 of first-degree murder for allegedly setting fire to the house of the town doctor, who had paraplegia and was trapped in bed when his house began to burn.

The motive was flimsy. Witnesses testified that the defendant’s mother, a nurse who worked for the victim, had threatened to kill the doctor a day or so before his death during an argument they were having. The defendant also had some criminal convictions in his past, but they were for minor offenses.

The blaze was inspected by the deputy state fire marshal. He had only been on the job 10 months, and his training had been limited to classes taught by his boss (the state fire marshal) and a two-week course at the National Fire Academy. Yet his testimony – as flawed as it later proved to be – was convincing.

The defendant was convicted and spent 14 years in prison before finally being freed by his own self advocacy and the work of some very dedicated outside parties. An investigatory analysis by an actual expert was also pivotal.

Tragic consequences for the wrongly accused

In 1991, a Texas man in his early 20s was convicted for intentionally setting fire to his home and, in the process, killing his three young daughters. The forensic analysis used to convict him was highly flawed, and advocates for the man later sought help from a renowned chemist who largely debunked the conclusions of the original analysis.

They submitted the findings to the Texas governor’s office and the board of pardons. The findings said the conviction was based on “junk science.” It’s not clear whether the report was even read, but the likely innocent man was nonetheless executed by the state in 2004. The man was only 36 and had already been in prison for more than a decade, accused of murdering his own children in a fire that was very likely an accident.

Check back soon as we continue this discussion in our next post.